When schools started banning jeans in the 1960s, most companies would have panicked. Not Levi’s. They said nothing and sales skyrocketed by 400%.

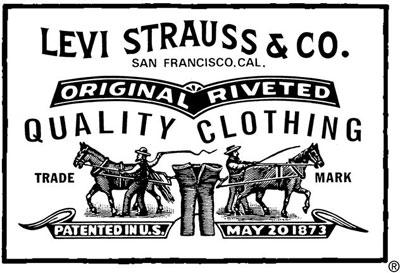

For 150 years, Levi Strauss & Co. has grown not by following the playbook, but by quietly rewriting it. At every turning point in its history, the company did what no one expected and built a $6.4 billion empire along the way.

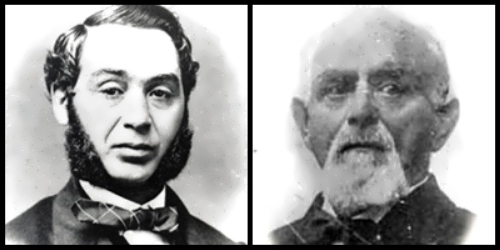

It began in 1873. In the mining camps of San Francisco, prospectors complained about their trousers tearing after just a few days of work. Every shopkeeper simply sold them more. But one German immigrant, Levi Strauss, asked a different question: Why not fix the problem?

The Secret Move of Levi Strauss

Together with tailor Jacob Davis, he created rugged work pants reinforced with copper rivets at stress points. Price: $3. The first “waist overalls” were sold to miners who had destroyed everything else they wore and they kept coming back.

Strauss didn’t just sell more pants. He sold permanence. And it turned miners into lifelong customers.

By the 1930s, Levi’s again refused to follow the obvious path. Back then, women who wanted sturdy trousers had no choice but to buy shrunken men’s clothes. The fashion industry assumed women didn’t need their own designs.

Levi’s disagreed. In 1934, it introduced Lady Levi’s, the first jeans made specifically for women’s bodies. Rivals laughed. Within 18 months, sales doubled.

Then came the 1950s and 60s, when jeans transformed from workwear to rebellion. Movie stars wore them. Teenagers wore them. And alarmed schools began banning jeans outright, claiming they encouraged bad behavior.

Most brands scrambled to apologize and distance themselves from controversy. Levi’s, once again, said nothing. The bans became their best advertising. With every headline, teenagers wanted jeans more and sales surged 400% without Levi’s spending a dollar on marketing.

But the toughest challenge came in the early 2000s.

Between 1996 and 2002, Levi’s sales crashed from $7 billion to $4.1 billion. Competitors offered endless styles, colors, and designer collaborations. Levi’s still sold blue jeans. Customers seemed to have moved on.

By 2011, some wondered if the brand had run its course.

That year, CEO Chip Bergh took over and doubled down on what Levi’s always did best. While consultants demanded variety, Bergh cut the product line by 40%, eliminated underperforming styles, and raised prices, even during a recession.

Instead of chasing trends, he invested $200 million into improving quality. It worked.

Today, Levi Strauss & Co. operates more than 3,400 stores worldwide, pulls in $6.4 billion in annual revenue, and enjoys margins most retailers envy. Its jeans are worn everywhere, from ranches to runways.

And all of this came not because they did more than others, but because they did what mattered better.

At each turning point, Levi’s asked one crucial question: What problem are we solving?

As others rushed to swamp the market with options, Levi’s kept a low profile working on creating the one product customers couldn’t do without and doing it so well they wouldn’t even think about switching.

The company’s narrative is a reminder to companies everywhere: sometimes the most daring thing you can do is say no. No to noise. No to unnecessary complexity. No to the easy way out.

Levi’s didn’t just make jeans. It made choices and stuck to them. And that may be its greatest legacy of all.

Also Read: Mohan Singh Oberoi: The Man Who Transformed Indian Hospitality