A viral LinkedIn post by Madhav Kasturia, founder-CEO of logistics startup Zippee, has ignited a fresh debate over how India’s quick-commerce platforms rank products and whether house brands are quietly crowding out legacy FMCG names at the very moment of choice.

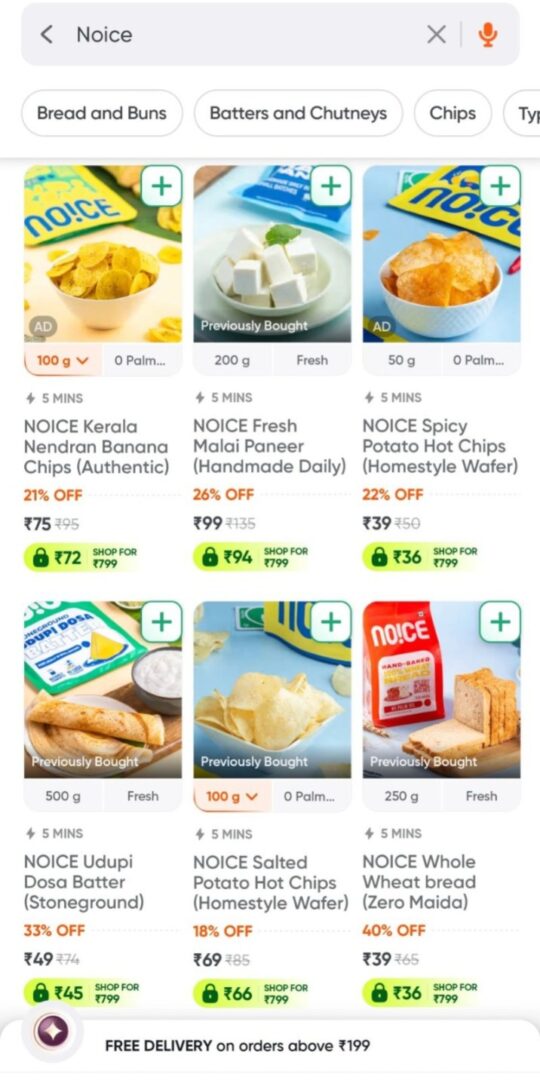

In his post, Kasturia argues that “Noice,” identified as Swiggy’s private label, consistently tops Instamart search results across everyday categories, from cookies and paneer to chips, often appearing above long-established brands such as Lay’s, Britannia and Amul. He frames the trend as “silent brand engineering through UI,” claiming that the path from data → visibility → purchase → repeat is becoming a defensible moat in quick commerce.

Kasturia also cites a user base of 2.4 crore (24 million) for the brand and situates the dynamic within a fast-growing market: Instamart revenue of ₹1,100 crore in FY24, quick-commerce GMV crossing ₹46,700 crore, and Instamart’s market share at roughly 26%, trailing Blinkit and Zepto. The thrust of his argument: while traditional FMCG players spend heavily to win shelf space and build D2C funnels, platforms can win at the point of choice by programming visibility inside their own apps, then fill that prime real estate with their private labels.

“Noice owns shelf,” Kasturia contends, adding that the products are marketed as small-batch, homestyle, and free of palm oil, positioned to match “instinctive taps, not nostalgia.”

Why this matters?

If accurate at scale, the behavior Kasturia describes signals a structural shift in FMCG power. For decades, the “shelf” was a physical rack negotiated through trade margins, distributor push, and expensive mass media. In app-led grocery, the shelf is the search bar and results ranking, and the gatekeeper is an algorithm the platform controls. A platform that both sells competitors’ goods and retails its own label can, in theory, self-preference, raising thorny questions about disclosure, consumer choice, and competition.

India’s competition regulator has previously scrutinized self-preferencing and ranking opacity in e-commerce. While quick commerce is newer and more localised than traditional marketplaces, the core risks rhyme: when the retailer is also a rival, every tweak to sorting, pinning, or default recommendations can tilt the field. Clear labelling, transparent ranking criteria, and fair-play guardrails are likely to draw more attention as private labels scale.

The platform playbook

Kasturia’s post outlines a familiar flywheel seen in global e-commerce:

- Data advantage: Platforms know what customers search, abandon, reorder, and how price-sensitive they are, often at SKU and locality level.

- Visibility control: Search defaults, top picks, and “bought together” slots become digital end-caps.

- Conversion loop: If private labels are positioned first, even modestly competitive price/quality can drive trial; repeat purchases then compound share.

For incumbents, the implication is stark: brand equity alone may not defeat default placement. Many FMCG companies have chased D2C funnels to regain first-party data and margins; but if a growing share of urban baskets is decided inside a few quick-commerce apps, the decisive battle shifts from ad spend to interface control.

The counterarguments and the fine print

- Consumer benefit vs. conflict of interest: Proponents of private labels argue that lower prices and faster iteration benefit consumers. Critics worry that if the referee is playing striker, rivals never see a fair ball.

- Quality and trust: Private labels must earn repeat purchases on taste, consistency, and safety, especially in fresh and dairy (paneer, for instance). If quality slips, visibility alone won’t sustain share.

- Disclosure duty: Transparent badging (“Swiggy-owned brand”), clear ranking parameters, and parity checks are essential to maintain user trust and avoid regulatory blowback.

What we can (and can’t) verify right now

Kasturia’s specific claims, Noice’s user base, Instamart’s FY24 revenue, quick-commerce totals, and Instamart’s market share, are attributed to his LinkedIn post. Independent verification wasn’t possible at the time of publishing here. The broader strategic thesis, however, that private labels can win via UI-level self-preferencing in quick commerce, aligns with well-documented patterns in online marketplaces globally.

Strategic takeaway for brands

For FMCG marketers, the message is unambiguous:

- Fight for coded visibility. Negotiate for transparent ranking logic, sponsored placements with clear disclosure, and performance-based visibility rather than opaque defaults.

- Diversify dependence. Build parallel pipes D2C, modern trade, ONDC experiments, and loyalty programs, so that discovery isn’t hostage to any single app’s algorithm.

- Exploit niches platforms under-serve. Distinct formats, provenance, and functional benefits (e.g., clean labels with real verification) travel well on social and retail media even if default slots tighten.

- Demand clearer labelling. If a platform sells its own brand, users should see it, loudly. Consumer trust collapses when lines blur.

Kasturia’s provocation ends on a warning shot: when the app stops being neutral, the “shelf” is no longer an open contest. Whether or not Noice is already the quiet winner on Instamart, the competitive logic he describes is the new reality of FMCG inside quick commerce: visibility is coded and ownership of the interface is half the war.

Editor’s note: This report analyzes claims made in a public social-media post by Madhav Kasturia. Figures cited above are his and were not independently verified.

Also Read: Zippee Founder Flags Safety Risks in PhonePe’s Pincode Healthcare